Most Favored Nation (MFN) pricing is bringing global pricing benchmarks into US drug pricing discussions, with meaningful implications for pharma asset valuation and deal economics. Yet the biggest blind spot is how MFN could change underwriting assumptions, deal structures, and risk allocation in M&A and licensing.

Most Favored Nation (MFN) pharmaceutical pricing (introducing international price benchmarks into US drug pricing for the first time) represents a monumental shift for global pharma. As the US currently pays substantially more for innovative drugs than other developed countries, the overarching goal of MFN is to rebalance this disparity. While much has already been written on MFN from a policy and regulatory perspective, its implications for pharmaceutical M&A and licensing deals and for how investors underwrite asset value and risk are still underappreciated. In this article, we focus on how MFN affects dealmaking, and the strategic considerations manufacturers need to address.

MFN background

MFN was first discussed in an Executive Order in September 2020, but was halted by legal challenges as well as a new Biden administration. A modified version was reintroduced in the second Trump administration with multiple executive actions in 2025, including: May 2025 Executive Order on MFN; letters to pharmaceutical manufacturers encouraging they adopt MFN pricing; a voluntary model for Medicaid (GENErating cost Reductions fOr US Medicaid) (GENEROUS), and mandatory models specific to Medicare Part B (Global Benchmark for Efficient Drug Pricing) (GLOBE) and Part D (Guarding U.S. Medicare Against Rising Drug Costs) (GUARD). Please see the graph below for an overview of these three models.

GLOBE | GUARD | GENEROUS | |

| Mandatory | Yes | Yes | No; voluntary participation |

| Focus | Medicare Part B 5-year rebate model | Medicare Part D 5-year rebate model | Medicaid 5-year rebate model |

| Scope | 7 USP DC categories and >$100M annual spend threshold ~25% of Medicare Part B FFS (i.e., not Med Adv.) beneficiaries identified via random selection of geographic areas | 17 USP DC categories and >$69M annual spend threshold ~25% of all Medicare Part D beneficiaries identified via random selection of geographic areas | Single source and innovator multiple sources covered outpatient drugs of voluntarily participating manufacturers |

| Market Basket | 19 high-income reference markets | 8 high-income reference markets | |

| Benchmark Price | Higher of Method I or Method II benchmark price:

| Higher of Method I or Method II benchmark price:

| Second-lowest GDP (PPP)-adjusted net price of the 8 reference markets (manufacturer reported) at the NDC-9 level (encompassing dosage form, strength, and route of administration) |

| Timing | October 2026 | January 2027 | January 2026 |

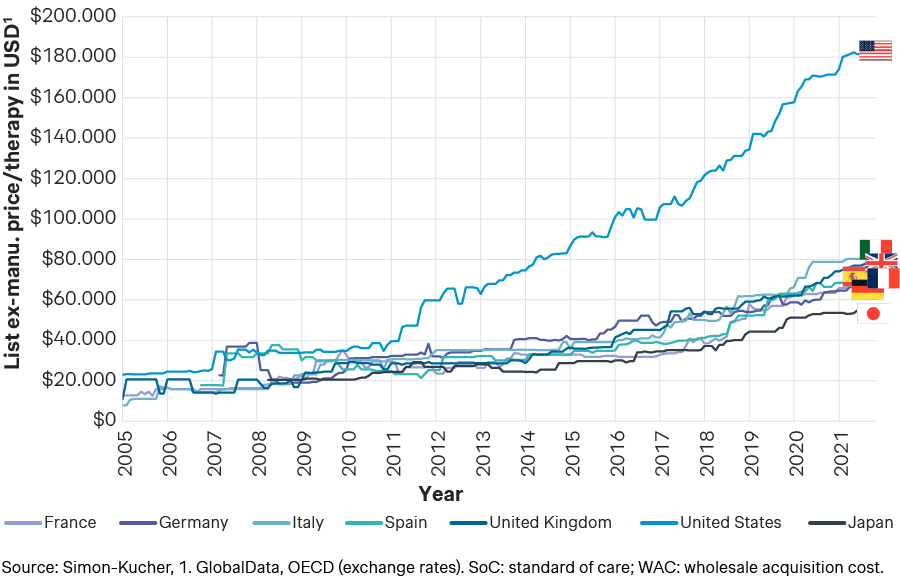

The US median annual list prices have increased significantly over time without commensurate meaningful increases in ex-US countries, emphasizing the impetus for MFN (see graph below).

Median annual WAC / list prices for oncology therapies, 2005-2021

This differential between the U.S. and ex-US pharmaceutical prices varies across therapeutic areas. For example, US drug prices are 4.8 times higher for cardiovascular diseases, but only 1.13 times higher for orphan diseases and 1.2 for hematology diseases.

Importantly, none of the MFN models imply full price convergence between the US and ex-US markets. Rather, they are designed to narrow the largest international price differentials in some US channels while preserving the US as the highest-priced market overall. For many innovative assets, ex-US markets still represent a meaningful share of long-term revenues, making these global pricing dynamics directly relevant for pharmaceutical acquisition and licensing decisions, asset valuation, and deal structure.

US payer mix determines the magnitude of MFN exposure

While MFN is often discussed at an aggregate US pricing level, its actual impact depends materially on the expected payer mix of a given asset. MFN-related mechanisms affect Medicare and Medicaid differently: the Global Benchmark (GLOBE) and GUARD models primarily apply to Medicare Part B and Part D, respectively, and are mandatory. In contrast, GENEROUS is a voluntary program targeting Medicaid pricing. As a result, MFN exposure can vary significantly across companies depending on whether they participate in GENEROUS, as well as across assets, indications, and patient populations.

For example, pediatric diseases typically have negligible exposure to Medicare, resulting in substantially lower MFN risk, particularly for companies that do not participate in GENEROUS. In such cases, indirect pressure on ex-US pricing is correspondingly reduced, improving the attractiveness of licensing or acquisition deals focused on ex-US geographies. By contrast, assets targeting elderly or chronic adult populations with high Medicare utilization face meaningfully higher MFN sensitivity.

MFN exposure is also shaped by therapeutic-area-specific pricing dynamics. Cardiovascular, diabetes, and immunology drugs often exhibit large US–ex-US price differentials (frequently >4x). Meanwhile, hematology, orphan, and cell and gene therapies typically show more compressed differentials (<2x). As a result, therapeutic area and asset type are critical inputs when assessing MFN-related deal risk.

Among the 16 manufacturers that have entered into dedicated MFN pricing agreements with the US government as of January 2026, MFN implementation may vary materially by company. For select manufacturers, the GENEROUS, GLOBE, and GUARD models may be applied in modified or bespoke forms, rather than as standardized programs. This introduces an additional layer of company-specific MFN exposure that investors must assess alongside asset- and indication-level risk.

For investors, this variability means MFN exposure cannot be assessed at a portfolio or company level alone but must be evaluated asset by asset as part of transaction diligence.

MFN is reshaping pharmaceutical acquisitions/licensing on both the buy- and sell-side

MFN has altered how manufacturers think about pharmaceutical acquisitions. Clients have increasingly approached Simon-Kucher’s Transaction Services and Private Equity team for due diligence expertise that incorporates an assessment of the target asset’s MFN implications.

MFN is sharpening the focus on how therapeutic value and unmet need translate into sustainable global pricing, particularly when ex-US markets are an important component of the deal value. Compounds that deliver high therapeutic value in areas of high unmet medical need are structurally better positioned to support attractive pricing and access in a future environment where ex-US prices may need to move closer to the US levels. By contrast, drugs that address indications with lower unmet need, or that primarily represent incremental alternatives to existing standards of care - where US-ex-US price ratios are often highest today - are likely to face greater difficulty achieving acceptable ex-US prices under MFN-linked reference dynamics.

From an investor perspective, MFN introduces greater uncertainty around sustainable global pricing assumptions, increasing the importance of scenario-based valuation, downside protection, and disciplined underwriting in acquisition and licensing decisions.

MFN and its impact on pharma asset valuation, M&A and licensing

Manufacturers have a range of possible strategies to best ensure success in dealmaking. One approach that Simon-Kucher has seen and supported more frequently has to do with deals that distribute risk across both the buy- and sell-side parties. Under these terms, deal economics may shift towards lower upfront payments but higher revenue-based payments after asset launch, accounting for a shifting pharma landscape due to MFN.

Additionally, manufacturers can consider blunting the overall impact of MFN for their acquisition and licensing deals by altering their approach to ex-U.S. geographies, potentially with strategies including:

Securing higher prices in ex-US markets (closer to the US) by focusing on drugs providing the highest patient value and building a strong dossier.

Securing higher prices in ex-US markets (comparable to the US) via lower volumes.

Engagement with governments advocating for favorable policy changes.

Innovative contracting models.

Launch sequencing and country (de)prioritization.

Of these options, securing drug prices in developed ex-US countries to be comparable to the US is especially vital to avoid unfavorable MFN reference pricing (Strategies #1 and #2 above). How this is executed, though, varies based on the target pharmaceutical’s clinical value.

For compounds providing significant therapeutic improvement, or addressing a high unmet medical need, manufacturers can develop strong evidence packages, consider outcomes guarantees, and build a robust negotiation platform (i.e., Strategy #1). Drugs that offer a comparatively lesser value to patients can consider lowering volume in exchange for a price in ex-US markets that is closer to the US price. For example, they can plan to limit the addressable patient population to only the highest-unmet medical need patients, or to patient subgroups where the drug provides the strongest efficacy profile (i.e., Strategy #2). This may be done by either pursuing a narrower regulatory label or proactively restricting the population to be reimbursed on the HTA/payer level.

Notably, only drugs that offer the highest value to patients in areas of high unmet medical need, and that show clinically meaningful differentiation against therapeutic alternatives, can secure broad patient access at an ex-US price comparable to the US.

Due diligences incorporating MFN assessments, US market expertise, and tailored ex-US evaluation are increasingly necessary for manufacturer success

In the long term, investors will need to evolve how they approach commercial and pricing due diligence assessments in the future. Asset valuation models that examine the US potential and then extrapolate to ex-US markets with an ‘adjustment factor’ are not viable.

Instead, investors must thoroughly evaluate both the US and ex-US potential with market expertise. This includes a robust understanding of product profiles at not only the efficacy and safety level, but also considering trial design, comparator selection, and endpoint selection, which is often heavily considered by European HTA bodies. And, critically, manufacturers must carefully evaluate MFN risks throughout their due diligences.

To discuss how you can realign your pharma pricing strategy to meet MFN-led shifts in the industry, reach out to our experts today.