Creating industry gravity: How certain companies or nations can reshape entire industries and economies.

Some companies and countries don’t just grow, they transform entire industries. Their scale, focus, and strategic coordination create ecosystems that attract suppliers, investment, and talent, setting off ripple effects across markets. South Korea’s auto industry, Taiwan’s semiconductor rise, and today’s AI sector all show how concentrated effort can turn a single initiative into a global economic force. Understanding how this kind of “industry gravity” forms is key for business leaders deciding where to invest, partner, or compete next.

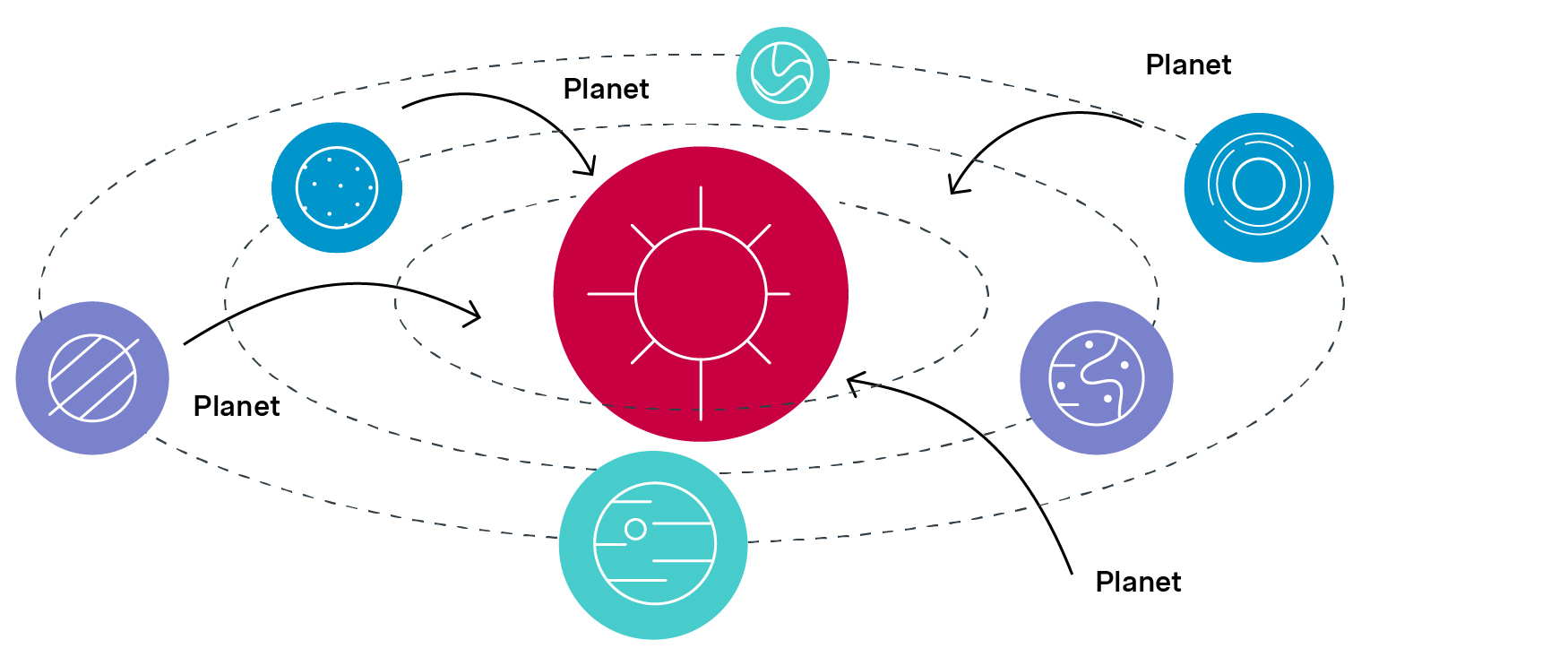

Think of Einstein’s theory of relativity, often explained using a simplified analogy: the rubber sheet.

| Imagine holding a stretched sheet in the air, then placing a heavy object, like a metal ball, at its center. The ball creates a depression, warping the sheet’s surface. When a smaller object is rolled across that sheet, it spirals toward the heavier mass and begins to orbit around it. In this analogy, the heavy object is the sun; the smaller ones are the planets. The gravitational pull isn't literal, but it helps explain why things don’t simply move in straight lines – they react to the shape of the space around them. |

Can companies and countries create their own sun?

Most business thinking still treats success as a competition on a flat field: gain market share, outprice, outmarket, outperform. The assumption is that everyone plays under roughly the same conditions. In reality, some companies change the conditions themselves. Once that happens, competition doesn’t look like a race anymore; it looks like orbit mechanics.

We see a version of this gravitational model in economics and business strategy. Some companies or industries don't just grow, they reshape the space around them. Their weight distorts the field. They become gravitational centers, pulling in suppliers, partners, startups, capital, talent, tools, and even regulation. Not all firms reach this level of influence, but when they do, they alter the trajectory of sectors, regions, and even global trade flows.

Automotive industry in South Korea

South Korea in the late 1960s provides a clear example of this. The country made a deliberate and aggressive investment in building an automotive OEM industry. Building cars isn’t just about assembling components. It requires orchestrating thousands of inputs: tires, seats, chassis, heating systems, wiring, electronics, logistics. It also requires the integration of suppliers, tooling, materials, and skilled labor. By centralizing its industrial effort around a singular focus, South Korea created a gravitational core. Tier-1 suppliers such as tire manufacturers, and upstream producers of cord fabric, nylon, and PET, began forming around the OEM nucleus. Over time, an entire industrial ecosystem was pulled into orbit. The result speaks for itself: in just a few decades, South Korea transformed from a low-income country to one of the world’s leading industrial economies, largely because it built its own sun.

Semiconductor industry in Taiwan

Taiwan experienced a similar process, but in a different industry. TSMC didn’t just become a globally dominant chip manufacturer; it became the sun of an entirely new industrial universe. Around it, orbits formed in EDA software, packaging firms, IP design houses, and research institutions. Unlike South Korea’s orbit, which remained mostly domestic, Taiwan’s sun pulled in international contributors. ASML in the Netherlands and Zeiss in Germany became essential components of the semiconductor ecosystem. The timing also helped. Taiwan’s ascent occurred in a period of intense globalization. South Korea had to pull everything inward; Taiwan could build its sun with global orbits.

Multiple sectors in China

Today, China is attempting to internalize its entire field of gravity. In industries like AI, semiconductors, and green energy, its strategy is to create the sun and keep the orbits local, controlling upstream materials and downstream platforms.

By contrast, many US and European companies once built powerful suns but let their orbits drift through outsourcing, offshoring, and IP leakage. The result is a world in which fewer economies host suns of their own. Most orbit someone else’s gravity.

AI today offers a live case of a sun in formation, pulling in industries like energy transition, data infrastructure, chip manufacturing, and software tooling. Each layer in the ecosystem grows and, in turn, reinforces the central sun.

What makes a company gravitational?

This leads to a deeper question: what makes a company capable of pulling others into orbit? What distinguishes a true sun from merely a successful firm?

Several factors distinguish these companies and explain their success.

- Global scalability: Not in terms of export volume, but in terms of problem relevance. Does the product or service address a universal need? Suns don’t just ship globally, they become globally necessary.

- Orbit formation: If suppliers, startups, universities, and tools begin to build around a company, even before it dominates the market, that’s an early gravitational signal. The iPhone wasn’t just shaped by Apple’s internal design team. It evolved through contributions in processors, battery tech, camera lenses, charging protocols, and interface design, all made by external firms. TSMC created its own orbits in EDA, chip packaging, design tools, and eventually, geopolitics. Gravity pulls the future into shape.

- Flywheel dynamics: A sun doesn’t grow linearly. It spins, faster and stronger. Each layer reinforces the next. Amazon didn’t just sell books. It brought in sellers, launched Prime, built AWS, and attracted even more sellers. Each orbit expanded the sun’s gravitational reach. That isn’t just growth. That’s gravity in motion.

We often assume that scale, capex, or global brand awareness are prerequisites. But they’re not. Consider supermarkets: they aggregate brands, products, logistics, and foot traffic. Consider IKEA. It created a global ecosystem of flat-pack furniture suppliers, logistics solutions, packaging standards, and in-store experiences. It didn’t rely on massive capital outlays, but it pulled the entire value chain into orbit. It acted like a sun, quietly but powerfully.

When growth becomes a gravity trap

A true sun enables orbits. It does not absorb them. Some heavily funded ventures failed because they lacked the essential traits of a true sun.

One of the clearest warning signs is over-centralization. Companies like WeWork collapsed under their own gravity by internalizing too much and leaving no room for external value creation. Blackberry, once a powerful sun, lost its gravitational pull by refusing to open its platform. Centralized scale is not the same as an ecosystem.

Another red flag is a weak core. A company cannot be the sun if it relies on external suppliers for critical IP, design, or technology. If the platform, innovation, or product architecture comes from someone else, the company is not the gravitational center. It’s simply a node in another firm’s orbit.

Finally, some companies display what can be called single-mode gravity. They attract capital, press, or talent but fail to produce a reinforcing ecosystem. They spike quickly and vanish just as fast. No reinforcing field forms around them. They are flashes, not suns.

Beyond profitability: Detecting early gravity

This brings us to an uncomfortable question: are our current evaluation methods preventing us from identifying or creating future suns?

Growth through these transformative companies was not driven by profitability or stability. They were anomalies: untested, unproven, misunderstood. But they shared one key trait: others began orbiting them before anyone realized they were the sun.

Common pitfalls when assessing growth

- Over-centralization

Leadership often manages companies to create a full integration to centralize everything within the company. This results in higher operational burden, limited focus and more importantly a compressed innovation in a smaller bubble that is bounded by only the vision of the main company. Innovation is too often mismanaged. It’s treated as an internal process when it should stretch across the entire value chain.

- Market share obsession

Many companies chase higher market share rather than focusing on solutions that address globally scalable, universally relevant needs. True value creation drives market share not aggressive commercial tactics. Share should follow gravity, not force. The differentiation gap between what competitors deliver is narrowing rapidly, making gravitational pull rather than marginal product superiority a more critical advantage.

- Applying yesterday’s metrics

Most companies today are assessed using a familiar checklist: strong EBITDA, predictable cash flows, modest growth, and low volatility. But the companies that became true suns rarely started that way. IKEA’s business model didn’t exist before it invented it. South Korean OEMs were seen as uncompetitive for decades. Semiconductors were viewed as capital-heavy, unstable, and fragile. Nearly every forecast about them was wrong. But in hindsight, we can see that signs of gravitational pull were already forming.

The future of growth

We must move beyond evaluating businesses solely on near-term profitability.

The better question is: are others beginning to orbit around them? That shift changes how we think about value.

The real challenge for strategists, investors, and policymakers isn’t just to find solid companies. It’s to detect gravity early before the light becomes obvious. This reframing could profoundly impact how investors, private equity, conglomerates, and corporate strategists allocate capital: not by traditional filters, but by identifying emerging suns.

Simon-Kucher helps leaders detect and amplify commercial gravity early by combining deep monetization expertise, behavioral insights, and data-driven growth strategy.

The result: stronger pricing, scalable revenue models, and earlier recognition of long-term value, well before the market sees the light.