The introduction of average sales price based reimbursement (ASP) in 2003, has brought about a challenging landscape for manufacturers of physician-administered medications. However, three lessons from high school physics can help manufacturers better understand provider contracting and manage long-term ASP.

One of the peculiarities of the US healthcare system is the handling of physician-administered medications. While a healthcare provider typically has no financial involvement in prescribing an oral medication, if the treatment under consideration involves a physician-administered medication, it can have financial implications for the physician.

Although there are certainly exceptions, in most circumstances for physician-administered medications, the physician practice will purchase the medication, administer it to patients, and then seek reimbursement from a third-party payer such as a health insurer or Medicare.

Metrics impacting provider reimbursement

Prior to the 2003 Medicare Modernization Act (MMA), physicians were typically reimbursed for these medications based on the Average Wholesale Price (AWP) or Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) of the therapy. Despite the nomenclature, these prices were not truly averages or wholesale costs, but more represented somewhat of a “manufacturer list price”, off of which manufacturers could choose to provide discounts to providers.

Since physicians were reimbursed for the medication at the list price, the difference between the list price and the actual provider acquisition cost was a source of margin – typically referred to as Net Cost Recovery (NCR) - for practices. In some circumstances, the discounts on therapies were quite significant, creating concerns that this practice could provide incentives that would influence physicians’ choice of therapy.

As foreshadowed above, the 2003 MMA instituted reforms which created a reimbursement limit within the Medicare program to 106 percent of the Average Sales Price (ASP).

Manufacturers are required to report the ASP to the Federal government every quarter. It consists of the actual average acquisition costs, subtracting out any manufacturer-provided discounts. This means that the spread between list price and physician purchase price was no longer a potential source of NCR, and physicians would instead be limited to a margin of essentially, on average, 6 percent of the purchase price.

The 2011 Budget Control Act, often referred to as the “sequester,” further reduced the Medicare reimbursement limit to 104.3 percent of the ASP, thereby limiting the NCR to only 4.3 percent.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were multiple attempts to increase reimbursement back to the original 106 percent, but these proposals were not able to pass through Congress. However, as part of the response to the pandemic, the reimbursement limit has temporarily been increased to 106 percent.

As defined in law, the Average Sales Price is indeed an average. That means that manufacturers are free to sell to different providers at different prices. In other words, the acquisition cost can vary across providers. However, since all providers receive the same reimbursement from Medicare, based on the average sales price to all providers, this leads us to our first lesson from high school physics – the First Law of Thermodynamics.

ASP and the first law of thermodynamics

The First Law of Thermodynamics states that energy is neither created nor destroyed, but can only be transferred form one form to another, or, as some like to say: “You can never get ahead, you can only break even”.

Similarly, when providing discounts to providers for physician-administered medications, margin is neither created nor destroyed, it can only be transferred from one provider to another. Any discount that is granted to one provider, increases that provider’s NCR, then reduces the overall ASP, the related ASP reimbursement limit, and, consequently, the NCR of all providers. To use another colloquialism: it is “robbing Peter to pay Paul”.

In setting up the system for ASP-based reimbursement, the government provided manufacturers and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) a period of two quarters to collect the data on ASP and determine the new CMS reimbursement limit. This means that there is a two quarter delay in the period between when discounts can be given to increase NCR and the subsequent decrease in the ASP reimbursement limit.

Once that reimbursement limit is decreased, physicians’ NCR is subsequently decreased. If manufacturers wish to maintain that NCR they need to give an even greater discount. This brings us to the second lesson from high school physics – the Second Law of Thermodynamics.

The ASP spiral and the second law of thermodynamics

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that there is a natural tendency of any isolated system to degenerate into a more disordered state, or in more colloquial terms: “not only can you not get ahead, you can’t even break even”.

Almost similar to the tragedy of opioid abuse, discounts produce a temporary “high” of an increased provider NCR, which must be followed up with greater and greater discounts to maintain that “high” and erode the overall level of ASP-based reimbursement.

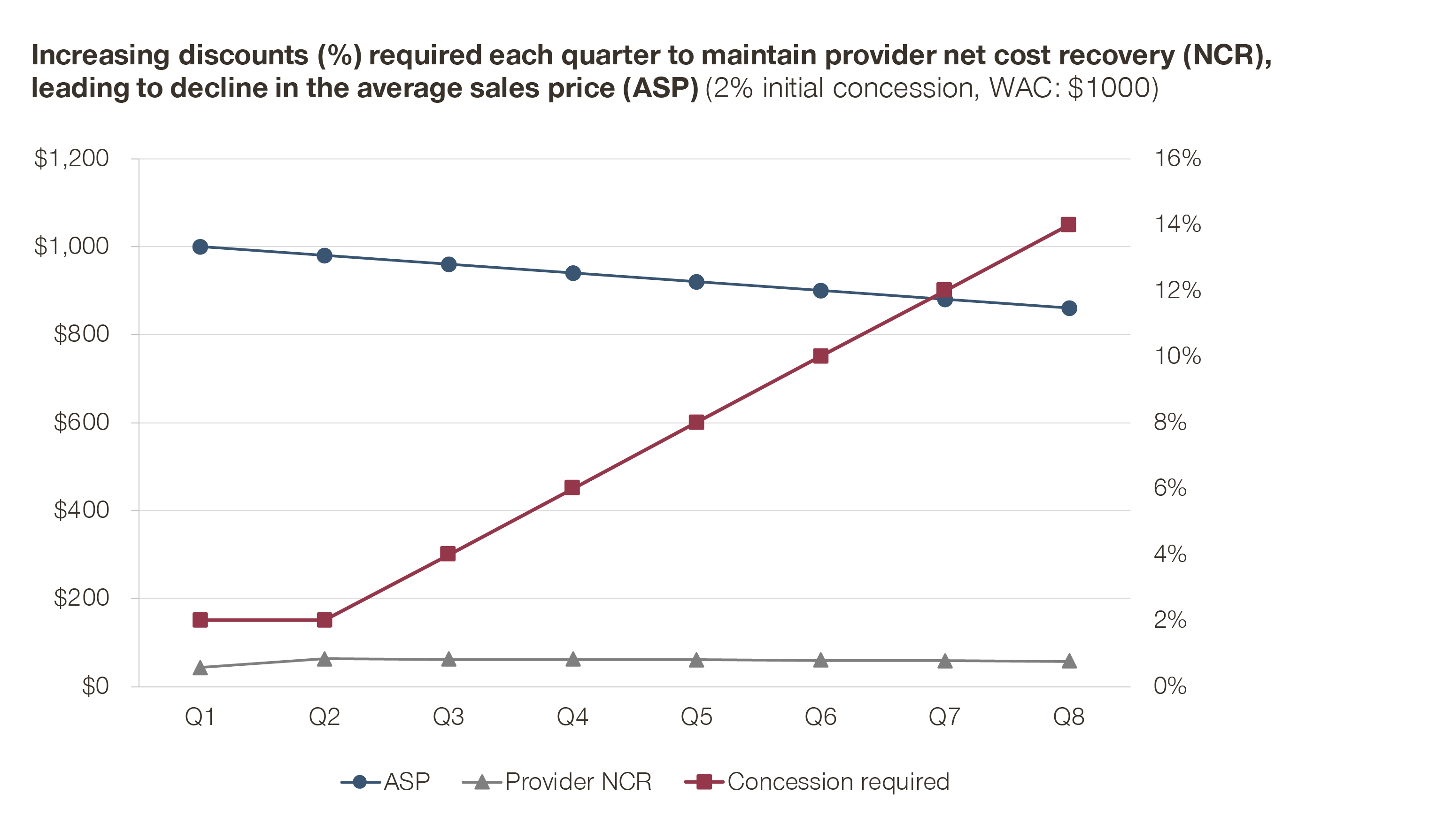

Figure 1 shows the impact on ASP over time of an initial manufacturer discount of 2 percent off the WAC price. The model assumes that, in order to maintain the same provider NCR, greater and greater discounts off the WAC must be provided.

Figure 1: Evolution of average sales price over time if the same provider net cost recovery is maintained.

Remedial measures and the third law of thermodynamics

Based on the first two laws of thermodynamics and the examples listed above, one might expect your ASP to freefall to a price of zero before too long. While the analogy is far from perfect, the Third Law of Thermodynamics provides us with some glimmer of hope.

The Third Law of Thermodynamics states that the entropy of a system approaches a constant value as the temperature approaches absolute zero – in other words, an infinite number of steps may be required to reach absolute zero. In the realm of provider contracting, there are some mechanisms that can help prevent ASP from quickly approaching absolute zero.

1. The type of concession

In the examples above, we have modeled the impact of immediate discounts on the invoice (sometimes also referred to as “off-invoice” because they are “off” the invoice price) on ASP. With this type of discount, the discount has to be accounted for in the same quarter as it is given.

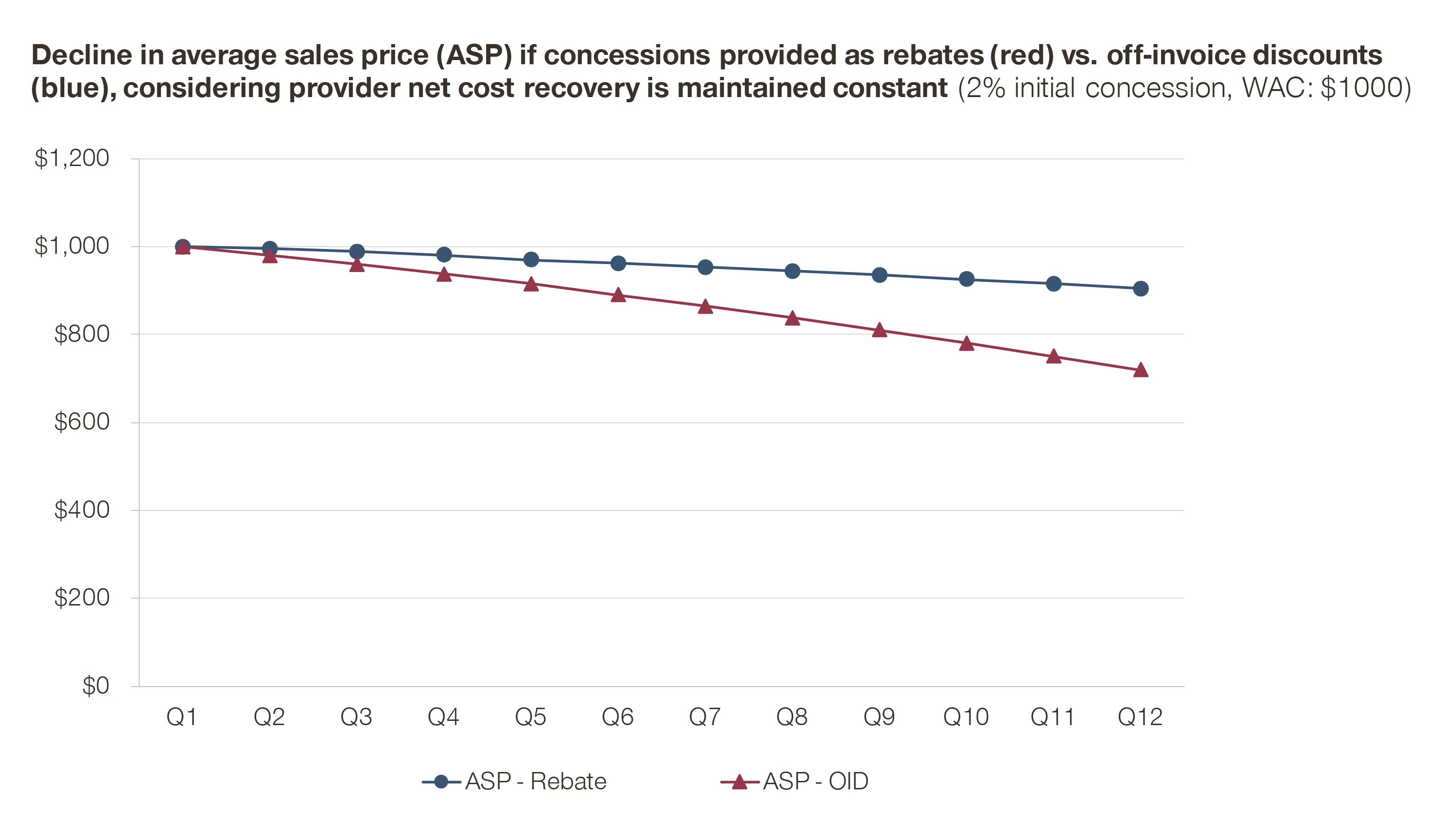

However, many manufacturers utilize back-end rebates – typically based on the volume of sales in a quarter – and provide the discount to the provider as a rebate. The value of these rebates do not have to be accounted for in the quarter they were given, but can instead be amortized over four quarters. This has a significant impact on reducing the steepness of the ASP decline (Figure 2). (Note: The term “concessions” hereafter refer to both discounts and rebates)

Figure 2: Impact of rebate vs. a discount of the same magnitude on the average sales price over time.

2. Beneficiary of the concession

It is important to leverage the power of price concessions only for those stakeholders who require it. Manufacturers should set up their concession program structure to impact decision-making among those who would hesitate to purchase on value alone.

A broad-brush approach allows for easy program set up and management, but dilutes the power of concessions and leads to unnecessarily giving away margin. A targeted program approach optimizes the use of concessions and reduces the overall magnitude of concessions given, reducing the impact on ASP and consequently the steepness of the ASP decline.

3. Need for the concession

Inspiration can be derived from two of Warren Buffet’s most popular pieces of advice: “Rule 1: Never lose money”, and “Rule 2: Never forget Rule 1”. Applying this advice to provider based contracting, one can extrapolate that whenever possible, do not give away margin.

Manufacturers should first assess the need to offer concessions, depending on the competitiveness of the landscape and the inability to differentiate based on product value alone. Non-monetary concessions, such as better customer support or priority supply, are also valuable to providers, and can help decrease the magnitude of monetary concessions given and attenuate the steepness of the ASP decline.

Conclusions

While provider contracting for physician-administered medications does present an added layer of complexity, there are some fundamental rules manufacturers should follow:

- Determine the need for concessions (i.e., difficulty in differentiating on value alone)

- Outline the objective and desired impact of the concession program (i.e., focus on penetration vs. being competitive in the market)

- Structure the concession program to prioritize certain beneficiaries (i.e., focus on impactful stakeholders vs. widespread adoption)

- Leveraging concessions types with the most impact (i.e., choosing rebates vs. discounts to reduce ASP decline and promote user loyalty, or complimenting the program with non-monetary concessions)

- Ensuring careful ASP management and monitoring (i.e., tracking long-term ASP evolution and amending the program to avoid major risks)

Much like the Laws of Thermodynamics in the physical world, understanding these fundamental rules can help manufacturers deftly navigate the world of provider contracting, ensuring positive momentum for one’s product with minimal exertion of force, and avoiding an absolute zero ASP.

For information other more nuanced levers that can be exerted to attenuate ASP decline, please feel free to reach out to the authors Nathan Swilling and Nikhil Pinto.